In this letter I would like to discuss the dynamics of economic growth and inflation that have been developing over the last three years. Much of this I have written about in prior investor letters; my goal here is to communicate and summarize my most up-to-date understanding of these dynamics and what this means for market expectations.

It is no secret that some events unfolded differently than I expected. This period has given me a greater understanding of inflationary dynamics that I hope to utilize in future investments. As always, my understanding of the situation will continue to evolve as new information comes in.

My purpose here is not to share new economic theories or proprietary research, but to show my investors the current paradigm in which I design my portfolio.

In 2020 we experienced an unprecedented flood of fiscal and monetary stimulus. It was during this time that my concerns over inflation were at their highest, as I anticipated the Fed to be extremely slow to raise rates regardless of the data. When rhetoric changed in 2021 and I realized the Fed would be reacting to the data after all, my concerns evaporated and I joined TEAM TRANSITORY.

This team (our team) got some things right and some things wrong. In terms of prices in the bond market, the team was clearly wrong.

So, what was right?

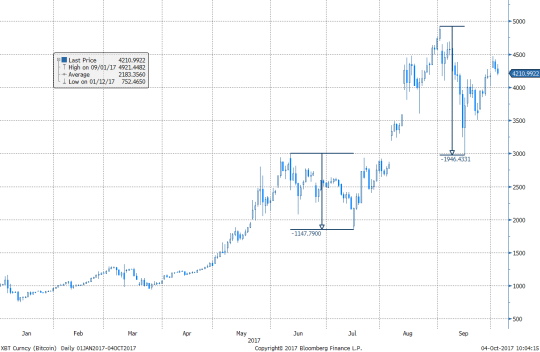

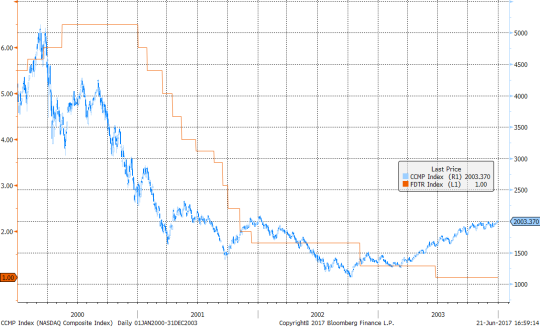

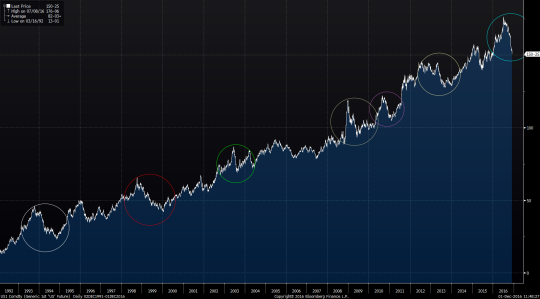

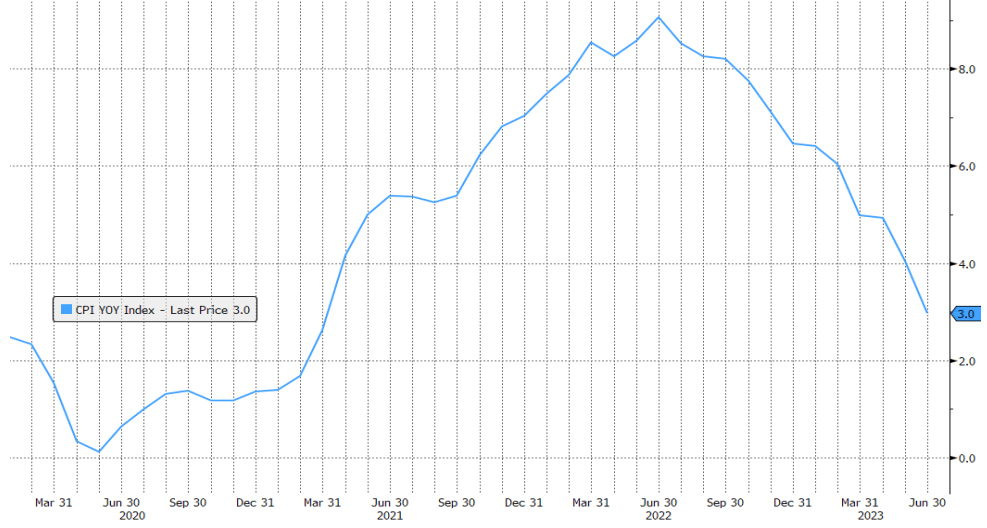

Team Transitory believed that post COVID-19 there would be a sharp spike in inflation, which would unwind just as sharply afterwards. This is indeed what happened and is demonstrated by the figure in Chart 1. I will discuss below why I am convinced that this unwind cannot be attributed solely to policy.

US Headline CPI YoY (%)

It is true the spike was even worse than many had expected, due to worse-than-anticipated supply issues.

However, the supply crunch and subsequent unwind would only reinforce the underlying thesis of Team Transitory.

So, what was wrong?

I was asked (I believe in late 2021) “at what point would Team Transitory throw in the towel?” My answer was, “Transitory is not about how long it lasts, but whether inflation is self-reinforcing or self-arresting.” There were various compelling arguments for both, but it was eventually determined that the inflation was self-reinforcing, which undermined the case of Team Transitory.

What we are seeing now are the broad lingering effects of 2021’s expansionary monetary policy (extremely negative real interest rates and QE persisting in the face of rising asset prices).

The important lesson was that it did not matter why inflation was high in 2021, as the policy rate stayed near zero. Supply-driven inflation, running at close to 9% annualized, metastasized in stickier areas of the economy, such as services, and fueled labor shortage and wage pressure.

Was the Fed wrong to keep rates at zero for so long? Most people would emphatically say yes. I am not so sure. For the reasons I will discuss below it may have been sufficient to just start unwinding the balance sheet earlier and more aggressively. The point, however, is moot. I am not in the business of advising central bankers. In either case, the Fed’s mandate is so nebulous that it is almost impossible to pass judgment on the efficacy of their policy. What is more important is to understand the timeline of the policy’s impact on inflation. Remember that Jay Powell himself acknowledges that the policy lags are “long and variable.”

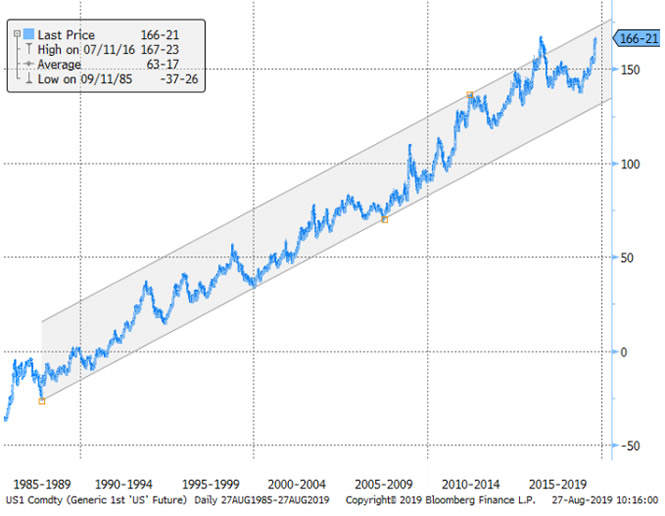

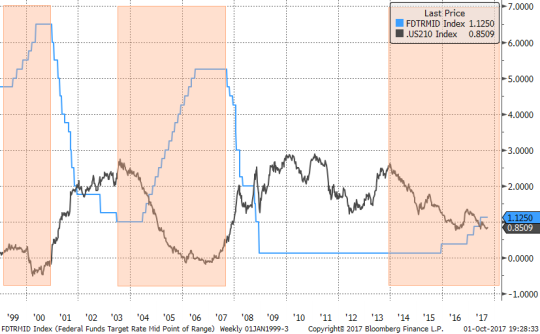

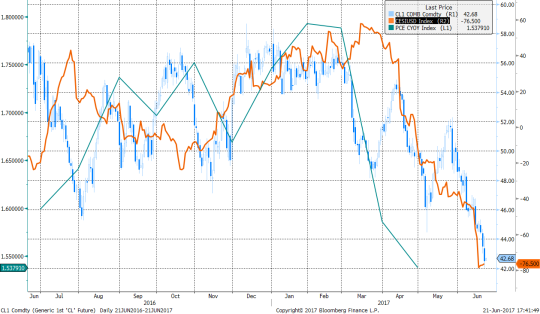

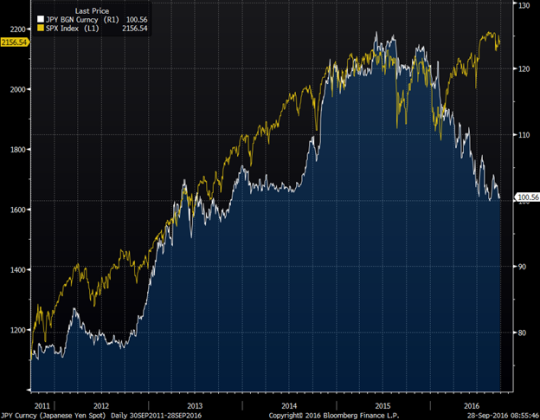

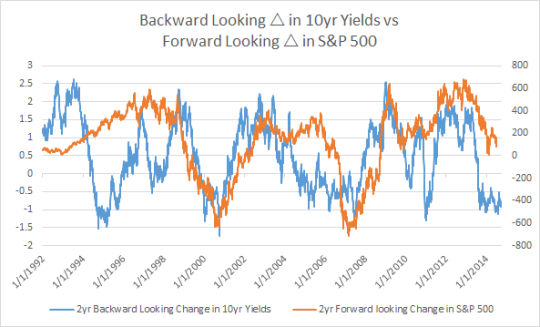

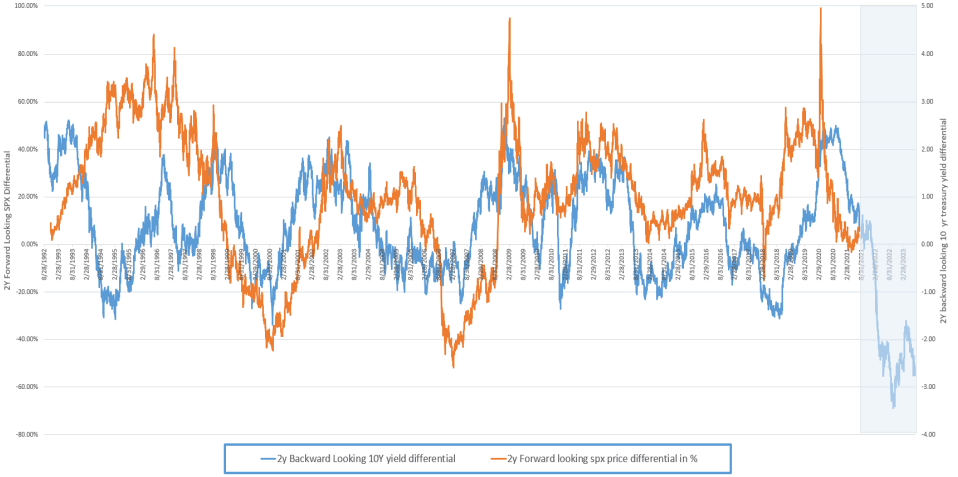

Notice, the peak policy impulse was in the spring of 2020 and peak inflation was in the spring of 2022. Those who follow my writing will recognize the magic two years: the lag between the interest rate momentum and the stock market momentum. This is demonstrated by what could be my all-time favorite chart.

2YR Backward Looking US 10YR Yield Differential vs 2YR Forward Looking S&P500 @ Change

It seems that the economy works in two-year cycle turnarounds. Correspondingly, the magic two years has been my favorite time horizon for trades.

Why is the lag so extreme? I am not going to analyze the economic process here, but I want to point out that peak policy impulse (i.e. the change in policy) is not the same as peak policy.

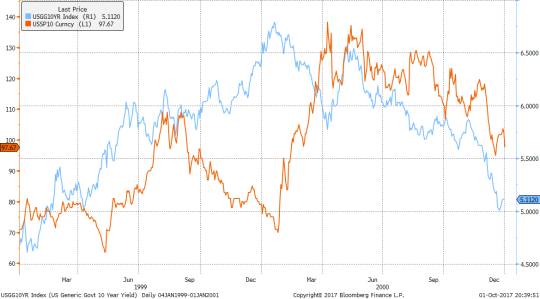

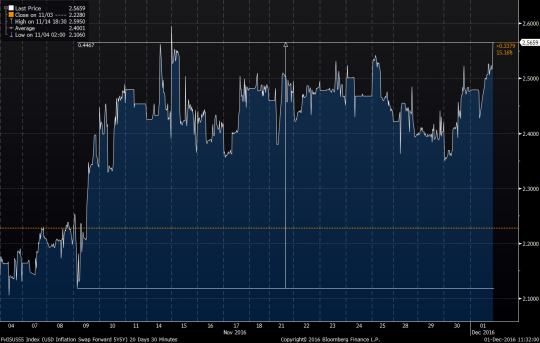

Indeed, the most amount of stimulus and the deepest rate cuts occurred in March 2020. However, due to the extreme deflationary impact of the pandemic, real rates were quite positive. The peak policy arrived in 2021, when inflation spiked and asset prices soared, while the rates remained at zero.

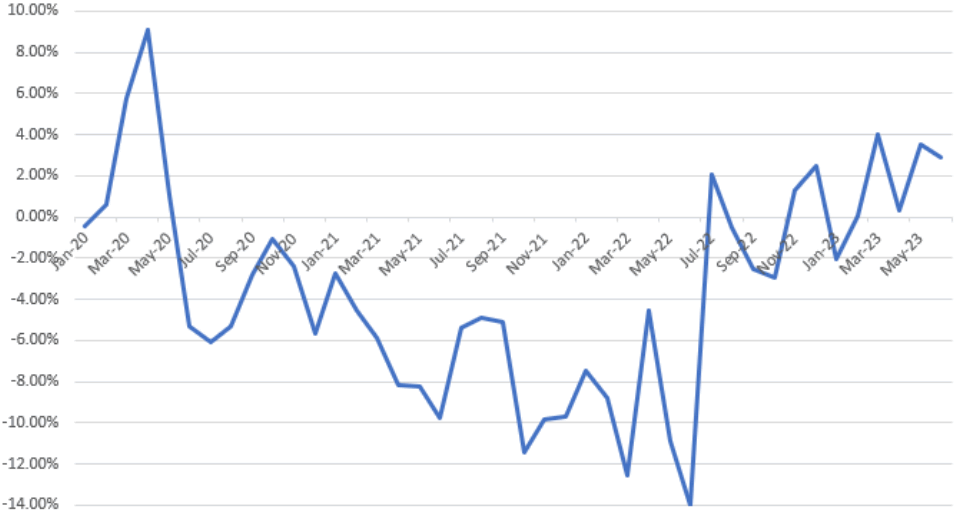

US Real Rate (Fed Fund Monthly Settle net Unrounded Headline CPI MoM Ann.), since 2020

Looking through this lens, the lag between the peak easy policy and peak YOY inflation was closer to one year!

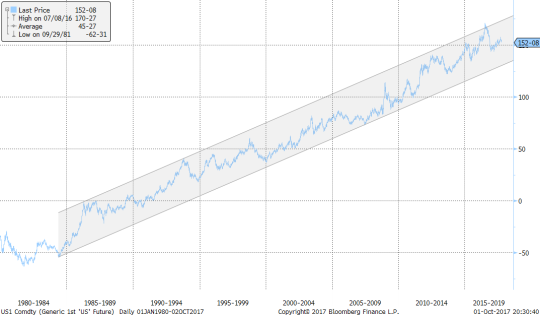

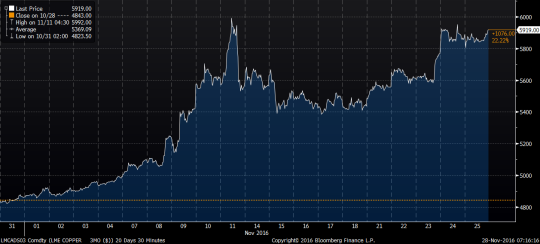

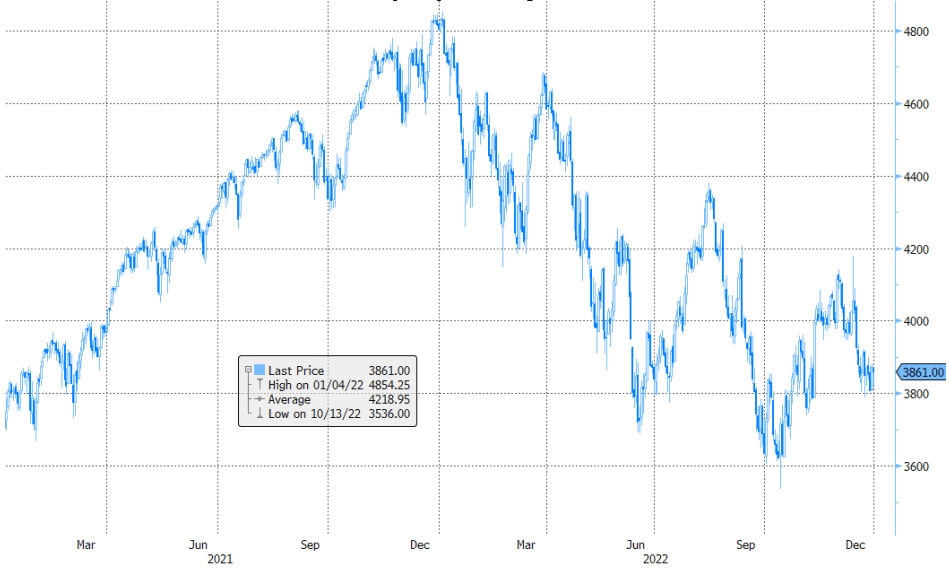

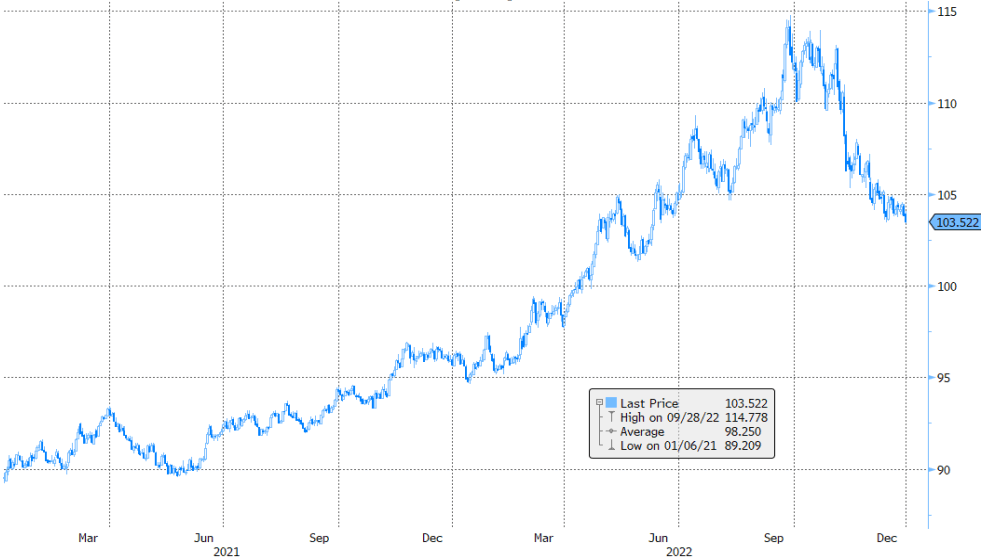

Let’s take it one step further. By mid-2022 I was convinced that the change in policy was getting traction. This was the time of the peak tightening impulse; the Fed was hiking at 75 basis per meeting, asset prices were falling, and the dollar was rallying.

S&P500 Future (ES1), roll adjusted, 2021-2022

US Dollar Index (DXY), since 2021-2022

Hence, I started targeting mid-to-end-2024 for peak deflation.

Notice that I am circumventing the Financial Condition Index as I don’t have much faith in its predictive power.

Rather, I would focus on the policy itself. In early 2022, the policy was not tight at all, and real rates were still very negative.

Then what about the economic slowdown and the technical recession of 2022? What about the marked decline of inflation between mid-2022 and mid-2023 that we referred to at the beginning of this letter? Enter again, Team Transitory. By any notion of the lag, those slowdowns could not have been the result of policy, but instead were the unwinds of the post-covid bumps.

Let’s return to our earlier observation: inflation is self-reinforcing. It doesn’t matter why headline inflation collapsed over the last year. The important thing is, with all else being equal, it will lead to further disinflation. This is where I come back to whether the extreme hiking cycle was necessary. Indeed, we have established that inflation has slowed down on its own and is feeding into lower inflation going forward. Raising rates now doesn’t aid this process, but only increases the risk of a deflationary bust in the future.

We hear a lot of talk about how we have likely avoided the recession. Honestly, I find such arguments nonsensical.

By which I don’t mean that they are a priori wrong, rather that they are completely unfounded. Only recently have real rates crossed into positive territory, and given the lag, how can we possibly know what effects they “had” on growth?

I believe what causes confusion is the order of events. We (myself included) have been trained to anticipate a particular pattern at the end of a business cycle:

- Interest rates rise

- Stock market crashes

- Economy slows

- Unemployment rises

- Inflation declines

However, somewhere between the economy slowing and unemployment rising the world failed to cooperate.

Why is it different this time? The pandemic crisis developed more rapidly than any prior recession and was met with an unprecedented amount of stimulus. The cash that was poured into the system by the government strengthened consumer balance sheets.

When rates go up it hurts those who need to borrow, but those who have excess cash or those who have already locked in low, long-term rates on borrowing (such as thirty-year fixed mortgages) come out just fine. Hence, the hikes didn’t immediately put pressure on (relatively) cash-rich consumers. Also, corporations boosted by the ability to borrow at negative real rates had no pressure to slow down hiring.

Moreover, the recent downshift in headline inflation, combined with the continuing tightness of the labor market, led to the increase in real wages and a further tailwind for the purchasing power of consumers.

Does this mean the economy is out of the woods? Not at all. The sentiment is positive, but if markets could thrive on sentiment alone bull markets and periods of economic expansion would never end.

The effect of higher real wages is almost immediate. Other effects of higher real rates may take longer to play out as money supply tightens. Even if the consumer and the stock market stay strong, fewer dollars in circulation will likely mean lower final demand in terms of dollars. It is hard to predict which shoe will drop first (like most, for example, I didn’t anticipate the regional banking crisis). Like in the game of musical chairs, if you keep taking dollars out of the system, sooner or later someone will come up short.

The pattern could be as follows:

- Interest rates rise

- Inflation declines and real rates rise

- Unemployment rises

- Economy slows

- Stock market crashes (or not)

I believe it is safe to assume the idea of a benign Fed pivot is a thing of the past. Given the policy lags discussed above, and the determination of the central bankers to see inflation fall to 2% before they take any easing action, it is almost impossible to hope the pendulum will not be allowed to swing too far in the deflationary direction.

In theory, the Fed would have to have already been cutting rates to match the disinflation. The reality is that they are still conducting QT as higher and higher real rates work their way through the system. As monthly inflation falls to zero and below, real rates will remain restrictive until the Fed cuts to zero and starts a new QE program. It is hard to imagine this transition occurring in time to avoid spiraling deflation.

One might observe that throughout this letter I have not mentioned any of the geopolitical, demographic, or technological factors which might affect the inflation outlook. There are two reasons for this.

First, is the time horizon. Over a two-year period cyclical forces tend to overpower secular forces, and at this juncture, I see cyclical forces as preeminent.

Second, the impact of secular forces is very hard to forecast. Consider the following examples:

- On-shoring and friend-shoring may be inflationary, but it may cause a severe recession in China. This in

turn would send a deflationary shockwave around the globe. - Green energy transition and lack of prospecting for fossil fuels may be viewed as inflationary, but in the

environment of tight dollar supply, high energy prices may slow global growth. - Baby boomers retiring leads to tighter labor markets but can also lead to lower consumption and lower

asset prices. - Generative AI may lead to a dramatic increase in productivity and be viewed as deflationary, but it can

also accelerate global growth and create new types of jobs.

I have also not focused on the fiscal impulse. Three reasons for that are:

- It is not clear whether it is more important that fiscal policy is still expansionary or that it is less expansionary than in 2020.

- Up until the next election the US Government is divided, limiting the ability for further stimulus until mid2025. Even after the election, the situation is hard to predict.

- Fiscal expansion without monetary accommodation may or may not be inflationary. Deficit spending is stimulative, but selling extra Treasuries to fund it might suck the money back out of the system.

Lastly, I haven’t discussed the “what if I’m wrong” aspect of my current portfolio construction. I believe there are good risk-reward trades currently available that take advantage of the environment in which my inflation outlook would be proven incorrect. My aspiration has always been to build as balanced a portfolio as possible. In this letter, however, I specifically express my views on inflation and duration.

I like to say that in the markets there are no certainties, only certain likelihoods. Hence, I would summarize the likelihoods I currently see in the following way:

- The inflationary cycle has swung in the direction of deflation and is currently self-reinforcing.

- It is too early to judge the effect of the hiking cycle on growth.

- During this cycle the slowdown in inflation will likely lead to the slowdown in growth via the mechanism of higher real rates.

- Secular and fiscal forces introduce uncertainties that I can’t measure, but I believe the cyclical deflationary forces will prevail over the two-year horizon.

- Faced with spiraling deflation the Fed will have no choice but to return to ZIRP, making long bond duration an excellent opportunity.

Good luck and stay healthy!

Alex Gurevich

Founder and CIO

HonTe Advisors, LLC