“Sour Grapes” is my response to all the complaining about central

banks (“CBs”) distorting markets, ruining price discovery, and leading their

countries into the hellscape of negative real rates.

Indeed, if global financial markets were a palace, the floors

would be sparkling clean: the central banks have been using their

counterparties as a mop for almost a decade.

Imagine this….

You are a monopolistic issuer of a product with nearly zero

manufacturing costs, i.e. fiat; and everyone wants to buy this product.

In fact, they are giving you real assets in exchange for it!

Your only worry in this dream-like scenario would be that at some

point the market is oversaturated with your costless product and its value

collapses, i.e. hyperinflation.

However, it doesn’t collapse!

And then it doesn’t collapse some more, and then some more, and

over time you accumulate trillions in real wealth on your balance sheet, which

was funded by the fiat you issued at the interest rate you controlled.

….

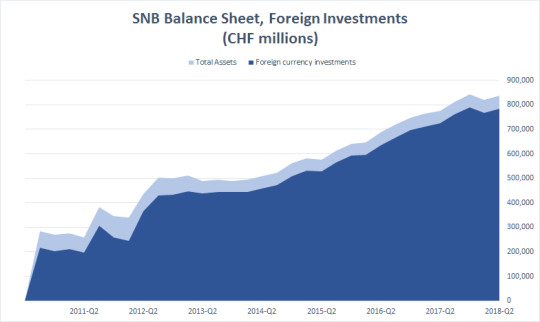

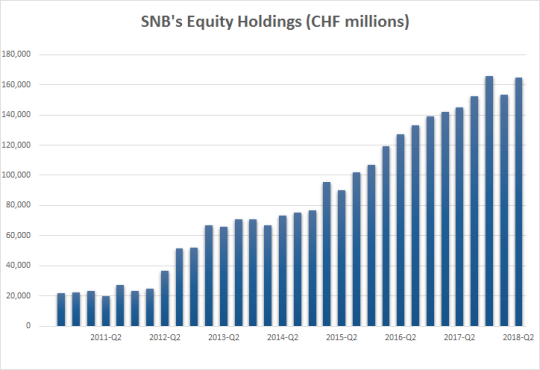

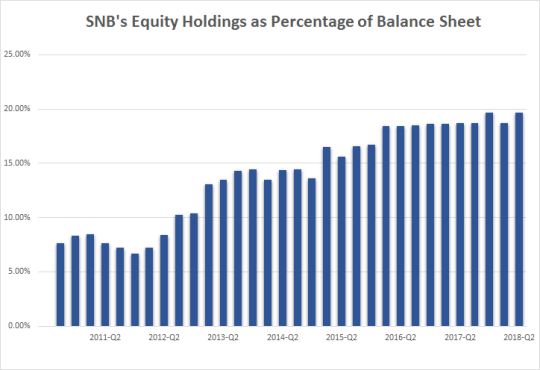

This is not fictional. The Swiss National Bank (“SNB”) has managed

to accumulate a huge fortune in foreign equities by printing Swiss franc, of

which the world doesn’t seem to have enough.

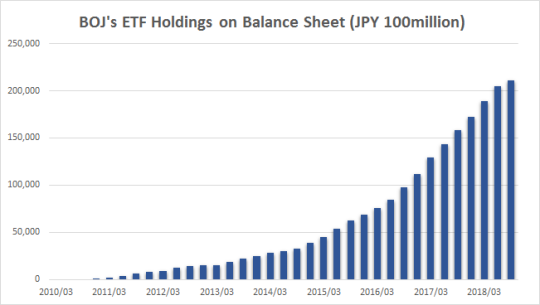

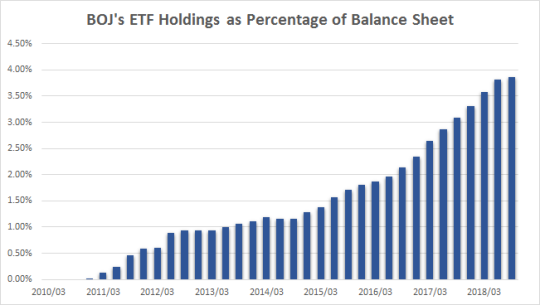

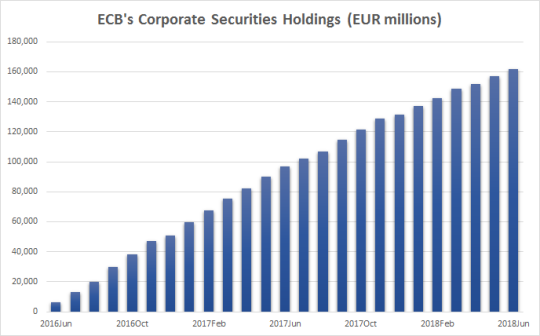

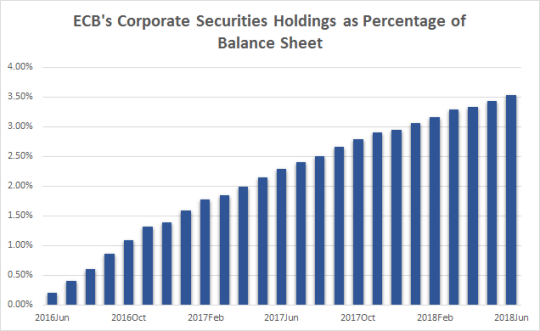

The Bank of Japan (“BOJ”) and the European Central Bank (“ECB”)

have also been voracious buyers of corporate securities.

*Only includes Corporate

Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP) of Asset Purchase Programme (APP).

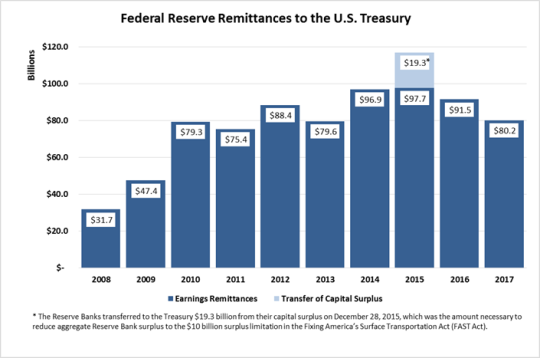

In the case of the Fed, one can argue that all they are doing is

exchanging the spurious dollar fiat for the equally spurious US Treasury (and

mortgage-backed) paper. Spurious or not, the Treasury has managed to fund the

fiscal expansion and many real-world expenses and projects, both useful and

otherwise.

And then during quantitative easing (“QE”) alleviated the burden

of outstanding debt in several ways:

- For years, the Fed paid just 0.25% on excess reserves and

was able to fund the bonds and remit the coupon proceeds to the Treasury. Such

remittances added up to $80-100bln a year (see Fed Remittances below). - QE (arguably) kept the interest rates lower allowing the US

to pay less interest on the new Treasury issuance. - QE pushed inflation incrementally higher, (also under dispute,

but somewhat likely given simple demand/supply considerations) driving the real

cost of borrowing even lower. In fact, negative for a long period of

time. - Possibly improved tax collection, as corporate profits were

aided by the lower interest rates and mortgage interest deductions were

lowered. At the same time the opposite side of this equation – interest

collected by savers – may be mostly tax sheltered in retirement accounts. Note:

A lot of maybes here, as I am not sure of this math.

I am not mentioning any benefits from domestic currency weakness

caused by QE given that with all major developed market central bank’s

simultaneously engaging in QE, this is presumably a zero-sum game.

At this point some readers are probably eager to assert that,

while the central banks have been presented as omnipotent thus far, their

comeuppance is imminent. In fact, many market participants adhere to the belief

that global fiat collapse is now unavoidable and hedge their risk by

stockpiling gold and cryptocurrencies.

In my view, while fiat collapse remains an existential risk to the

global financial system, the current evidence points towards the opposite. We

are not faced with the question of whether the world will absorb the increasing

supply of cash; the world did absorb it. And the central banks, who have

managed to sell it, are now armed to the teeth to defend it.

Indeed, if, as in the case of the USA, cyclical inflation raises

its head and the economy appears in danger of the overheating, central banks

can simply start buying their fiat back. Or, in other words, reduce their

balance sheet – which is exactly what the Fed is doing with quantitative

tightening (“QT”)!

In this process, the assets on the CB balance sheet become exactly

what they are called….ASSETS.

These assets can be and are used to defend the credibility of fiat

by giving it a consistent bid.

Furthermore, if, in cases such as Switzerland or Japan, the

domestic currency was to suddenly spiral down under the weight of increasing

monetary base, the CHF and JPY could be defended by selling foreign assets.

On the flip side, the ownership of domestic sovereign debt by the

CB can be used to mitigate excessive currency strength and a deflationary

spiral as well. The BOJ, ECB, SNB and Fed all have the ultimate stop-gap of

full or partial debt jubilee as described by David Zervos in his “Bondfire of the Vanities” discussion.

Some of you may have noticed, that there is one scenario none of

the above measures would help with…Stagflation.

Personally, I am inclined to believe that stagflation is a

mythical creature, or at least an urban legend.

I know, I know, there are historical examples. (Wait, are there?).

But looking back through my couple of decades in financial

markets, everywhere I turn I see robust growth and moderating secular

inflation. The opposite of stagflation.

Of course, it is possible that the end of both the secular trend

of disinflation and the secular bull market in sovereign debt is here and now.

But I just fail to see the evidence.

Inflation remains moderate, despite a quite prodigious effort to

inflate DM economies. And where, like in the USA, cyclical inflation becomes a

threat, the policy quickly gains traction and flattens the yield curve.

And this is all happening in an environment of a very long

economic expansion. Why should I believe that inflation will become a threat in

a downturn?

Suppose I am wrong. I still struggle to see how the Fed’s large

balance sheet is a problem.

It is a problem if you are forced to sell assets when their prices

are going down. But central banks are never forced to sell, because they

control the funding.

In the hypothetical stagflationary scenario, the CBs will have a

range of possible policy options. They, for example, can

choose to keep rates very a low (even negative) to ameliorate an economic

slowdown and reduce their balance sheet to support domestic currency and

mitigate inflation.

Notice the Fed started to do things in the opposite order (e.g.

hikes first), because stagflation is not a current concern.

All of those arguments are based on the assumption that central

banks are run by intelligent people invested in the long-term prosperity of

their country. Some readers may take an issue with this assumption and if you

feel inclined to have your views swayed by this post, I would also recommend

reading Fed Up: An Insider’s Take on Why the Federal Reserve is

Bad for America, where Danielle DiMartino

Booth presents a very different perspective.

The question of benevolence of the CB policy ties to an inquiry:

who are the aforementioned hapless counterparties? Are they just reckless hedge

fund managers going short US Treasury bonds or stocks? Or, are they the

domestic savers, including pension funds, who are deprived of yields? Or even

the millennials staring at the absurd housing prices and the absence of ways to

build wealth? Or maybe the 99% watching global monetary flows slip between

their fingers and stream into the vortex of economic singularity?

Preferring to keep the discussion strategic rather than political,

we still have to confront the trope of central banks being run by clueless

academics. Academics tend to be bright and open-minded by virtue of being

academics. Sure they don’t have a good grasp on how the real markets operate.

But neither does everyone else, including economists, strategists, financial

advisors and journalists, politicians, entrepreneurs, and corporate executives.

Anyone without experience as a global macro trader, who must contend with

interconnected financial markets, is comparable to a general who has never

fought in a war.

Yet, some generals trained in peacetime have done well. And those

“clueless academics” pulled off the greatest coup in financial history.

It is my belief that QEs were genuinely intended to, and succeeded

remarkably at, promoting the wealth of their respective nations. Any

disappointment in how this extra wealth ended up being distributed is neither

strictly within the purview of a central bank nor within the scope of this

post.

From a strategic perspective, I am only disappointed the Fed

didn’t cut rates much faster in the end of 2007, didn’t start QE earlier in

2008, and, more importantly, didn’t pursue an even more immense and broader

scale of purchases. Stronger and quicker action may have ameliorated the Great

Recession, but even if it were ineffective, I don’t see how it could have been

detrimental to the recovery.

This relatively trivial critique only confirms the success of the

CB strategy: of course, no matter how much of a profitable trade you put on,

you end up wishing you had it in a larger size.

It’s possible to debate whether the trading success of the CBs can

be evaluated on the same scale as that of other market participants. On one

hand, the CB buys and sells at market prices as everyone else, and their

product, fiat, is transparently presented. On the other hand, they are embedded

in their government, flanked by politicians, the military, and law enforcement

who protect their credibility.

Fair or not, one has to play the hand they are dealt.

And the central banks are not just playing the game well….THEY

HAVE ALREADY WON!

Good luck,